The readymade, as coined by Duchamp, is essentially an ordinary manufactured object displayed as a work of art, in which the artist's sole intervention is limited to its placement and title. The readymade raises the question of choice as an aesthetic act. According to Duchamp, "The choice of the readymades is always based on visual indifference along with the total absence of good or bad taste."

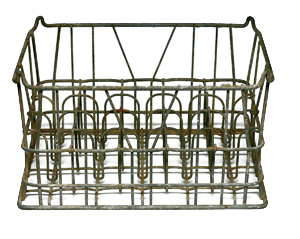

Duchamp's famous Bicycle Wheel (Roue de bicyclette, 1913), misinterpreted for its direct subversiveness, is one of the first emblematic works to be called a readymade after 1915. However, an even earlier work, predating this, has recently come to light; the previously lost Milk Carrier was revealed to the art world in 2005, nearly 100 years after its realization.

John Mills was a London collector and close friend of the artist. In a letter dated July 1912, Duchamp asked Mills to select an object in London and send it to him. The object arrived six months later. It was unwrapped, examined and approved by Duchamp, who then sent it back to Mills accompanied by a letter describing the transformation process by which this object became a work of art. Although Milk Carrier was neither selected by nor even exhibited by Duchamp, it nevertheless took its place in a corner of the home of the collector, who it is believed never realized the significance of the piece yet treasured it instinctively.

The full story finally emerged in 2005, when the Mills's grandson and heir to the collection happened upon the correspondence between the two. This correspondence became the first "Certificate of Authenticity" for a work of modern art. "Must the artist select the ready-made, or does merely approving it suffice?" Duchamp inquired of Mills in a letter. Besides this correspondence, no other evidence has been found connecting Duchamp to this object.